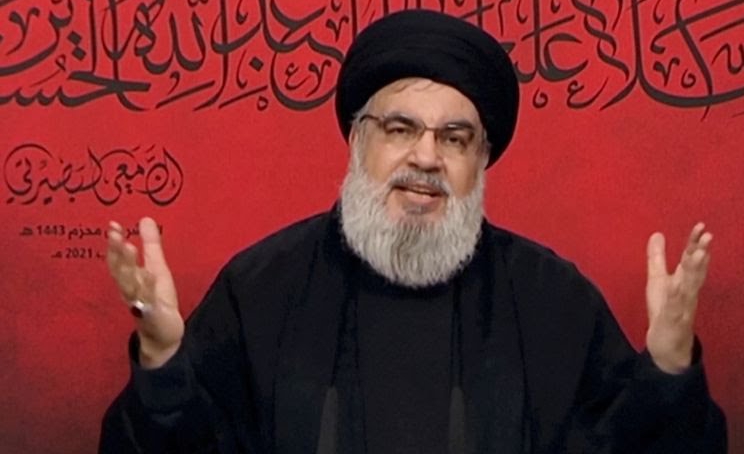

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah

How Israel strike kills Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah leader, in Beirut

Hassan Nasrallah, the longtime leader of Hezbollah, was killed in a massive Israeli air attack on Beirut on Friday evening, the Lebanon-based group has confirmed.

The Israeli army had claimed the assassination earlier in the day.

Nasrallah, who reached the peak of his popularity after the war with Israel in 2006, was seen as a hero by many, not just in Lebanon but beyond. Standing up to Israel is what defined him and his Iranian-backed group, Hezbollah, for years. But that changed when Hezbollah sent fighters to Syria to crush the uprising threatening President Bashar al-Assad’s rule.

Nasrallah was no longer seen as a leader of a resistance movement but the leader of a Shia party fighting for Iranian interests, and was criticised by many Arab countries.

Even before Hezbollah’s involvement in the war in Syria, Nasrallah had failed to convince many in the Sunni Muslim Arab world that his movement was not behind the 2005 assassination of Lebanon’s former prime minister, Rafik Hariri. An international tribunal indicted four members of the group for the murder and one was later convicted, Al Jazeera reports.

Despite this, Nasrallah continued to enjoy support from his loyal base – mainly Lebanon’s Shia Muslims – who revered him as a leader and religious figurehead.

Born in 1960, Nasrallah‘s early childhood in East Beirut is cloaked in political mythology. One of nine siblings, he is said to have been pious from an early age, often taking long walks to the city centre to find second-hand books on Islam. Nasrallah himself has described how he would spend his free time as a child staring reverently at a portrait of the Shia scholar Musa al-Sadr – a pastime that foreshadowed his future concern with politics and Shia communities in Lebanon.

In 1974, Sadr founded an organisation – the Movement of the Deprived – that became the ideological kernel for the well-known Lebanese party and Hezbollah rival, Amal. In the 1980s, Amal mined support from middle-class Shia who had grown frustrated with the sect‘s historic marginalisation in Lebanon, to grow into a powerful political movement. Besides commandeering an anti-establishment message, Amal also provided stable income to many Shia families, unfurling a complex system of patronage across Lebanon‘s south.

After the outbreak of civil war between Lebanon‘s Christian Maronites and Muslims, Nasrallah joined Amal’s movement and fought with its militia. But as the conflict progressed, Amal adopted a staunchly unsympathetic stance towards the presence of Palestinian militias in Lebanon.

Disturbed by this stance, Nasrallah split from Amal in 1982, shortly after Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, and formed a new group with Iranian support that would later become Hezbollah. By 1985, Hezbollah had crystallised its own worldview in a founding document, which addressed the “downtrodden of Lebanon“ and named the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran as its one true leader.

Throughout the civil war, Hezbollah and Amal evolved in bitter tandem, often jostling with each other for support among Lebanon‘s Shia constituents. By the 1990s, after numerous bloody clashes and with the civil war over, Hezbollah had largely trumped Amal for prominence among Lebanon‘s Shia supporters. Nasrallah became the group‘s third secretary-general in 1992, after his predecessor, Abbas al-Musawi, was killed by Israeli missiles.

Since early in his career, Nasrallah‘s speeches helped cement his persona as a wise, humble figure, deeply invested in the lives of everyday people – a leader who shunned formal Arabic in favour of the dialect spoken on the street, and who reportedly preferred to sleep, every night, on a simple foam mattress on the ground.

In the book The Hizbullah Phenomenon: Politics and Communication, scholar and co-author Dina Matar describes how Nasrallah‘s words have fused political claims and religious imagery, creating speeches with high emotional voltage that transformed Nasrallah into “the very embodiment of the group”.

Nasrallah’s charisma was far-reaching; his elegies on the history of oppression in the Middle East have made him an influential figure across sects and nations. That was helped by Hezbollah‘s sprawling media apparatus, which makes use of TV, print news and even musical theatre shows to spread its message.

When Nasrallah took on the position of secretary-general, he was charged with easing Hezbollah into the melee of Lebanon’s post-war political scene. Hezbollah went from working outside the official enclosure of state politics to becoming a national party asking for every citizen’s support by participating in democratic elections.

Presiding over this shift was Nasrallah, who put Hezbollah on the ballot for the first time in 1992 and appealed to the masses in rousing speeches. As he told Al Jazeera in 2006, “We, Shia and Sunnis, are fighting together against Israel,“ adding that he did not fear “any sedition, neither between Muslims and Christians, nor between Shia and Sunnis in Lebanon”.

As the head of Hezbollah for more than 30 years, Nasrallah was often described as the most powerful figure in Lebanon despite never personally holding public office. His critics said his political muscle came from the weapons Hezbollah held, and that it has used against domestic opponents, too. Nasrallah repeatedly turned down calls for his group’s disarmament, saying, “Hezbollah giving up its weapons … would leave Lebanon exposed before Israel.”

In 2019, he criticised nationwide protests calling for a new political order in Lebanon, and Hezbollah members clashed with some protesters. That dented his image among many in Lebanon.

But Nasrallah’s supporters still saw him as a defender of the rights of Shia Muslims, while his critics accused him of showing allegiance to Tehran and its religious authority whenever their interests contradicted with those of the Lebanese people.

Hezbollah faced one of its biggest challenges after the group opened up a front against Israel to help relieve pressure on its ally Hamas in Gaza, in October 2023. The group suffered losses after months of cross-border fighting and Israeli attacks that targeted significant figures in the movement. But Nasrallah remained defiant.

While Nasrallah has been described as the “personification of Hezbollah”, the group he built over more than three decades is highly organised and remains determined to continue standing up to Israel.

Hezbollah is unlikely to crumble under the weight of Nasrallah’s assassination, but in his death, the group has lost a leader who was charismatic and whose influence extended far beyond Lebanon. The group will now need to select a new leader, who in turn will need to decide what direction to take Hezbollah in. Whatever the group decides will affect more than Hezbollah: ripples will be felt across Lebanon and the wider region.